All aboard the gRPC train

Introduction

During my internship at Datadog this past winter, I took ownership of a critical service which handles around 40,000 requests per second as of April 2018.

To improve its reliability and fault tolerance, I migrated the service’s inter-process communication (IPC) layer from Datadog’s homegrown remote procedure call (RPC) framework to gRPC, an open-source RPC framework made by Google.

Context

The service is deployed on more than 200 nodes and it is consumed by approximately 500 other instances. It comes with a client library. Consumers of this service can simply use this client library to issue RPCs without worrying about service discovery, (client-side) load balancing, generating stub, error handling, etc.

My task was to deprecate this client library, and to migrate its consumers to use gRPC to communicate with the service instead.

However, deprecating a legacy package is never easy. There are always undocumented edge cases. Blindly replacing an old system with a new one may result in regressions (old bugs reappear).

Tests and CI are in fact designed to mitigate this problem. However, in a large-scale distributed system, certain tests (for example, load tests) are not practically possible to be included in the CI pipeline.

To fully understand the old system and to ensure that there is no regression

after the migration, I had to go through the service’s outage docs, reinforce

the monitoring system (metrics, logs, tracing), and design chaos testing

(iptables/pkill -9 server instances).

In this post, I won’t go into details about how I carried out the migration (maybe another post!). Instead, I would like to discuss why it was worth the effort to migrate to gRPC.

The Old Framework

Originally, consumers communicate with the service using an in-house RPC framework. It was built on top of the Redis protocol to take advantage its rich ecosystem and mature tooling. This made sense years ago when Datadog’s infrastructure was not as complex or extensive.

However, the framework was not optimized for large-scale distributed systems. In a distributed system, network is never reliable and nodes can fail unpredictably and independently due to hardware faults or human errors. Reliable software tolerates faults. The in-house RPC framework, however, does not provide any mechanism to make the inter-process communication more reliable.

Unreliable Health Check

A service registry is essentially an eventually consistent snapshot of the current state of the system. It should absolutely not be regarded as the only source of truth.

For example, when a node suddenly becomes unresponsive (the process gets pkill

-9‘ed, node is running out of file descriptors, etc), it will take seconds or

maybe even minutes for the service registry (health check service) to realize

that the node is dead. And it will take more time to propagate this (sad) news

to every node in the system.

Therefore, when a consumer of a service retrieves a list of “healthy” nodes from the registry, the list could contain false-positive, already-dead nodes. The question then arises: how to ensure RPCs to only be sent to actually healthy nodes?

Transient Errors vs Fatal Errors

This is where the legacy RPC framework falls short. The framework is unable to identify the type of fault that causes an RPC to fail.

A fault could be transient, which means that if the client waits for a moment and retries (resends the previously failed RPC) to the same server node, it will eventually succeed.

On the other hand, an RPC failure can also be caused by a fatal error. This may imply that the destination node is dead. When a fatal error is identified, the client should send the RPC to another node, instead of retrying on the same node.

Poor Error Handling

Now, let’s go back to the old framework. Since it was not built for distributed systems, being able to identify the cause of a RPC failure and handle it accordingly was not possible. (That’s why people say programming distributed systems is hard! This problem would be trivial if everything happens in memory)

As a result, the legacy RPC framework simply sends the failed RPC to a different node returned from the service registry.

This approach can lead to many problems. For example, clients can run out of instance-wide retry budget quickly. Assume RPCs have locality (eg. client-side load balancing with consistent hashing). If a server node fails, all the RPCs that are mapped to that node will fail on the first attempt, and then retry.

In addition, if there are more than one false-positive nodes returned from the service registry (eg. when doing a rolling restart), the second attempt (the retry) may fail as well.

Fault Tolerance

Let’s say the service registry returns n “healthy” nodes, and among them,

there are x false-positive nodes. Assume we use the old

retry-on-a-different-node error handling technique and assume that we balance

the load randomly. The probability of the client to send a RPC to a bad node is

x / m.

The client will then retry on a different node. Now, the probability to hit

another bad node becomes (x - 1) / (m - 1). On kth retry, the probability

becomes (x - k) / (m - k).

If you are good at math, you will quickly see that if our retry budget is

greater than x (assume x < m), we can guarantee that all the RPCs will

eventually succeed.

In other words, the system’s fault tolerance is linearly dependent on the retry budget––the total number of failed nodes the system can tolerate literally is equalled to the retry budget. This is clearly not scalable because retries are expensive.

Having an aggressive retry strategy can result in server resource exhaustion which can then leads to cascading failures. On the other hand, conservative retries can exhaust client’s resource (because of back-offs and jitters) which limit the throughput per instance.

A fault tolerant system does not only minimize errors but also minimizes retries.

Node Outage

Node outage is also a tricky problem in distributed systems. For example, after the TCP handshake has been completed and the client has sent the request payload to the server, if the server node suddenly fails before it can respond to the RPC, the client may hang indefinitely. Although the server is dead, from the client’s perspective, the server may be processing a time-consuming query. In other words, there is no way for the client to identify the cause of an unresponsive node.

One of the common solutions is to set a RPC deadline based on the expected response time, which is typically estimated from the size of the request payload. If the deadline is exceeded, we can be confident to assume that the server is faulty. This distinguishes infrastructure faults from application faults. However, it is impossible to implement this functionality in the old RPC framework.

gRPC Comes to the Rescue

gRPC is a remote procedure call framework developed at Google. It has been adopted at many organizations including Netflix and Square.

Similar to the homegrown RPC framework, it exposes an API to generate stubs, integrate with the existing service discovery system, etc. But different from the legacy framework, gRPC is optimized for large-scale distributed systems. It has a huge emphasis on reliability and fault tolerance.

Connection State Management

Instead of treating the service registry as the absolute source of truth, the gRPC client library implements a connection state manager to maintain a pool of guaranteed healthy connections (sorta like a circuit breaker).

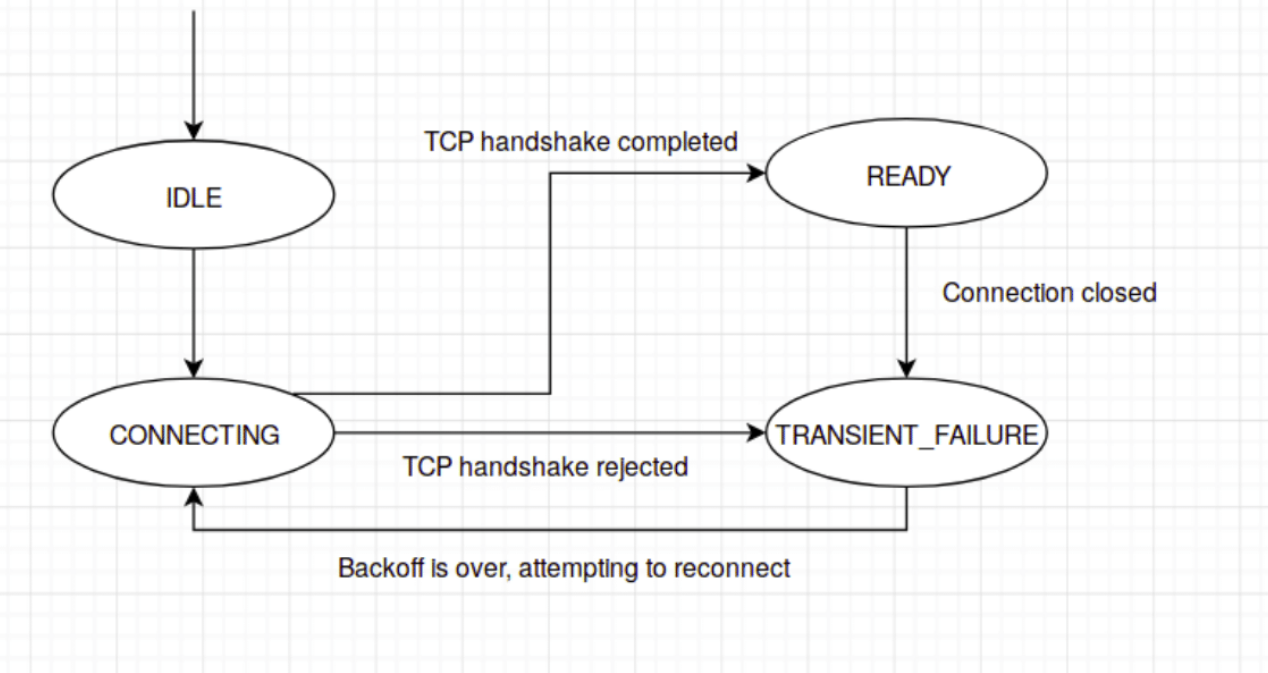

On initialization, the gRPC client library instantiates a state machine for each

node returned from the service registry. The initial state for all the nodes is

IDLE. If the gRPC client successfully establishes an connection (completes the

TCP handshake with the target node), it will transition the connection state to

READY. If the connection request is rejected or the connection is detected to

be faulty, the connection state will be transitioned to TRANSIENT FAILURE.

When a TRANSIENT_FAILURE connection is reestablished, it will be transitioned

back to READY.

Source: gRPC Connectivity Semantics and API

This way, especially with consistent hashing, when the gRPC client detects that

a node is in TRANSIENT_FAILURE (even though service registry says it’s

healthy, but it is unresponsive in real life), it will simply remove the node

from the list of “buckets”. As a result, RPCs which were originally hashed to

the failed node will be rehashed to a different but healthy node. This

significantly reduces the total number of retries.

RPC Deadlines

Deadlines and timeouts are pretty much the same…

With gRPC, it is also possible to dynamically set a deadline for individual RPCs. Setting a deadline allows the client to specify how long it is willing to wait for the server to process its request. This can effectively distinguish between fatal failures and long running queries.

For example, if an RPC hangs, there are two possible causes:

- The query is very expensive and it will take a while.

- The server is dead

For the first case, we only need to wait longer. On the other hand, as for the second case, we do not want to wait at all. We should cancel the RPC as soon as possible. RPC timeouts & deadlines helps to distinguish between the two causes.

We can estimate the maximum response time for a particular request with a certain payload size. Then we can derive the timeout from it. Thus, when an RPC fails because the timeout is exceeded (or deadline expired), we can be pretty confident to say that the server node is faulty (outcome #2) and we want to cancel the RPC and retry on a different node.

Application-Level Keepalive

In addition to the configurable RPC deadlines. gRPC also implements a application-wide keepalive protocol, which further increases the fault tolerance to failed or unresponsive nodes.

For example, if the server appears to be unresponsive for a certain length of

time, the application-level keepalive, also known as the gRPC keepalive, will be

activated. The gRPC client will send a keepalive ping to the server. If the

server does not respond on time, the client will terminate the connection and

transition the state of that connection to TRANSIENT_FAILURE to remove it from

the healthy connection pool.

This distinguishes infrastructure faults from application faults. In the case of a long-running RPC, the server will be able to reply to the keepalive ping so the client may wait longer. On the other hand, if the server is dead, the client can be confident to terminate the TCP connection and retry the RPC on a different node.

Gains

It is hard to measure resiliency gains (can’t really say I increased the

resiliency by 34.5% or decrease the number of future outages by 29%).

However, there is in fact one notable gain, faster deployment!

Faster Deployment

Deploying a service typically requires all its instances to be restarted with a new binary. However, depending on how stateful is that service, a restart can result its instances to be unavailable for a length of time. For zero downtime deploys, instances are typically restarted in batches, so that at a given time, there are always enough instances that are available to serve requests.

Before gRPC is introduced, the maximum number of node failures the system tolerates could not exceed the RPC retry budget. As a result, to minimize errors, instances had to be restarted one at a time. This is not scalable because a service’s deployment time becomes linearly dependent on the number of instances of that service! As for the service I owned at Datadog, with approximately 200 instances and a 10-second warm-up time, it can take more than 30 minutes to deploy!

With the migration to gRPC and the increase in fault tolerance, instances can be restarted in larger batches, which significantly speeds up the deployment time.

More Reliable Performance

The response time of an RPC is the time between when the client initializes the request and when the client actually receives the response. If an RPC fails and the client decides to retry, the retry back-off time also contributes to the response time of the RPC.

Therefore, retries can directly impact a system’s performance. Previously with the old RPC framework, an unresponsive node can result in a large number retries or hanging RPCs. A rolling restart or independent node outages can potentially affect the throughput of the system.

The migration to gRPC greatly mitigated this problem. Thanks to gRPC’s per RPC timeout, we are completely immune to hanging RPCs. The number of retries is also minimized with the connection state management feature.

Conclusion

In this post, I talked about the problems with distributed systems and how gRPC improves fault tolerance by mitigating these problems. This is also my first distributed systems blog post. Thanks so much for reading!

Recently I have been reading Martin Kleppmann’s Designing Data-Intensive Applications and I was fascinated by the distributed data section. I find replication algorithms, consistency models, consensus protocols, etc., to be very interesting. Hopefully I can work on another distributed system for my next internship and gain experience in working with distributed data.